the many faces of endometriosis:

the struggles of unseen, underdiagnosed and underrepresented women.

I was 10 when I got my first period, but the pain wasn’t always debilitating.

I was 12 when it was so excruciating, I found myself curled in a ball in my primary school's first aid office.

After half an hour, I staggered out to the front desk and asked if they’d called my mum to pick me up.

They told me to “give it a bit longer” and sent me back to the bed.

Years later, I learned that the school hadn’t even called home yet. I don't know whether they weren’t bothered, or thought a sobbing, year-six child was faking. But I was doubled over when my mum finally arrived, immediately after being called.

I was 14 when I started taking a hormonal contraceptive pill to manage my period pain.

At 16, I got a contraceptive rod to supplement the pill. My arm was bruised for weeks. Still, I once bled for four weeks straight.

At 18, two weeks after my birthday, I had laparoscopic surgery to excise the endometriosis in my pelvis. Getting a diagnosis was a relief.

Two weeks later, I completed my trial HSC exams.

Now, I’m 19, and get injections every 10 weeks.

All this to stop the symptoms, to stop the endometriosis from growing bit by bit, each time I menstruate.

And still, I consider my experience to be a breeze, compared to what some women go through.

Bruising, one week after getting the Implanon rod in my arm. (Supplied: Erin Symes)

Bruising, one week after getting the Implanon rod in my arm. (Supplied: Erin Symes)

After my surgery (Supplied: Erin Symes)

After my surgery (Supplied: Erin Symes)

One week after surgery, with a catheter bruise still on my hand. (Supplied: Erin Symes)

One week after surgery, with a catheter bruise still on my hand. (Supplied: Erin Symes)

My healing scars, exactly six months after surgery (Supplied: Erin Symes)

My healing scars, exactly six months after surgery (Supplied: Erin Symes)

Showing off my surgery outfit, compression socks, little booties and cap, two hours before my surgery. (Supplied: Erin Symes)

Endometriosis is when tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows outside the uterus. It affects over 10% of Australian women and can cause pain, infertility, fatigue, digestive issues, heavy bleeding and more.

Considered ‘elective’, laparoscopic excision surgery is the gold-standard in diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. It involves putting a telescope through the belly button and/or stomach incisions. However, very few doctors are experts, and even fewer are public. Fifty-eight percent of women's endometriosis-related hospitalisations in 2021-2022 were partly or fully funded by private health insurance, while 10% of women funded their experiences entirely by themselves. In one year, Australian women spent $220 million on endometriosis.

Though a chronic, incurable, and reoccurring illness, education and awareness occurs predominantly amongst non-medical professionals, like Facebook support groups, ‘nurses-turned-activists’, and word-of-mouth.

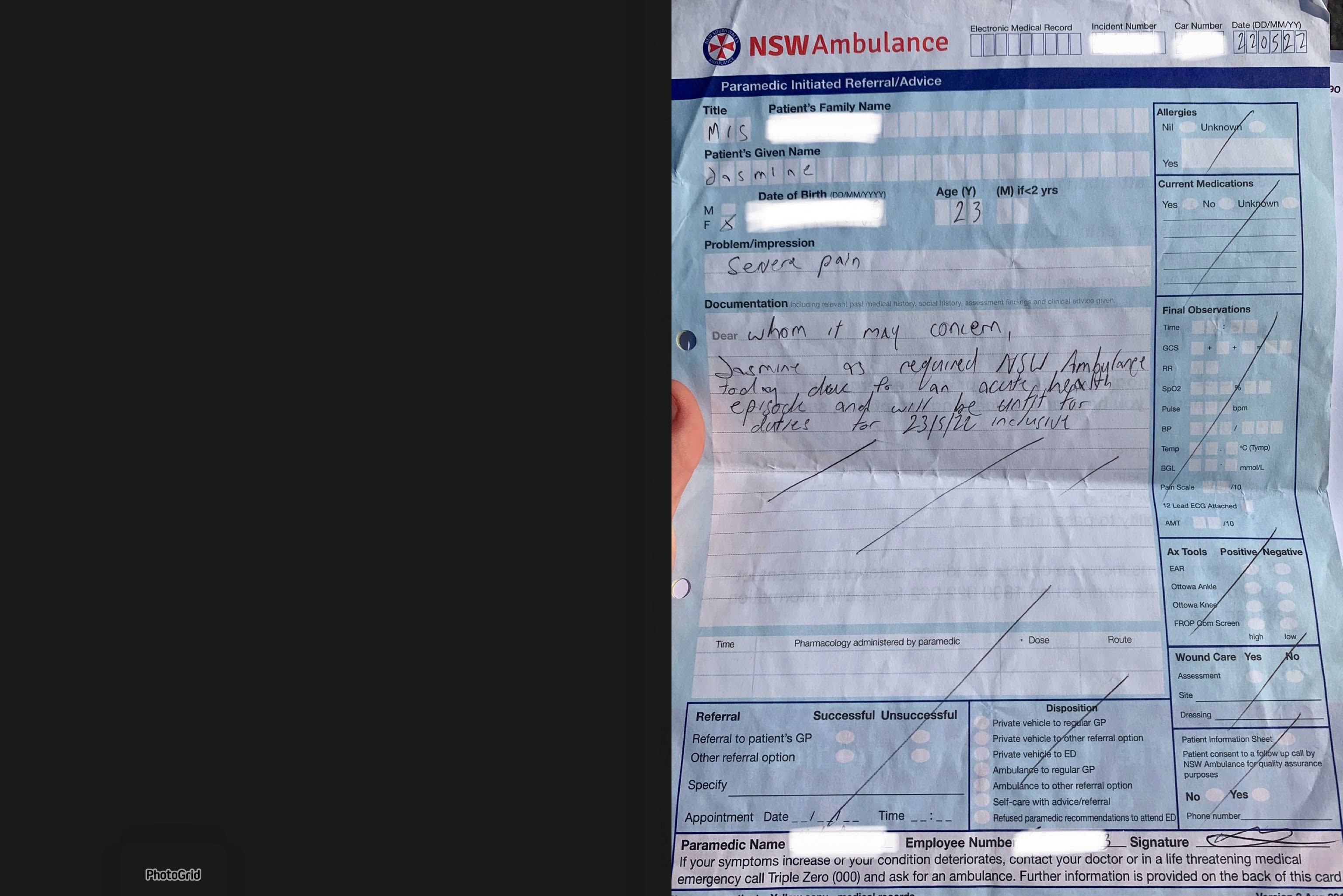

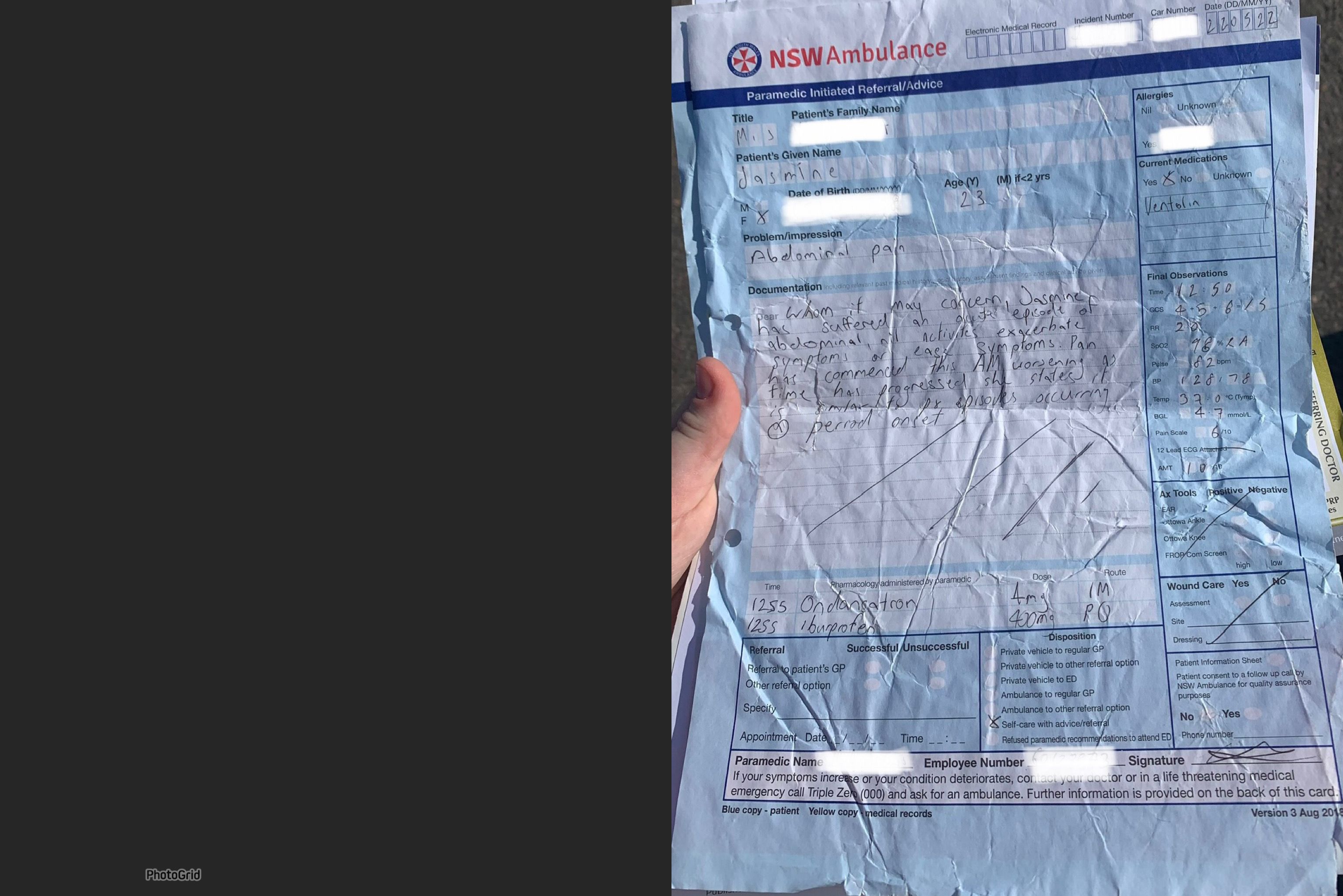

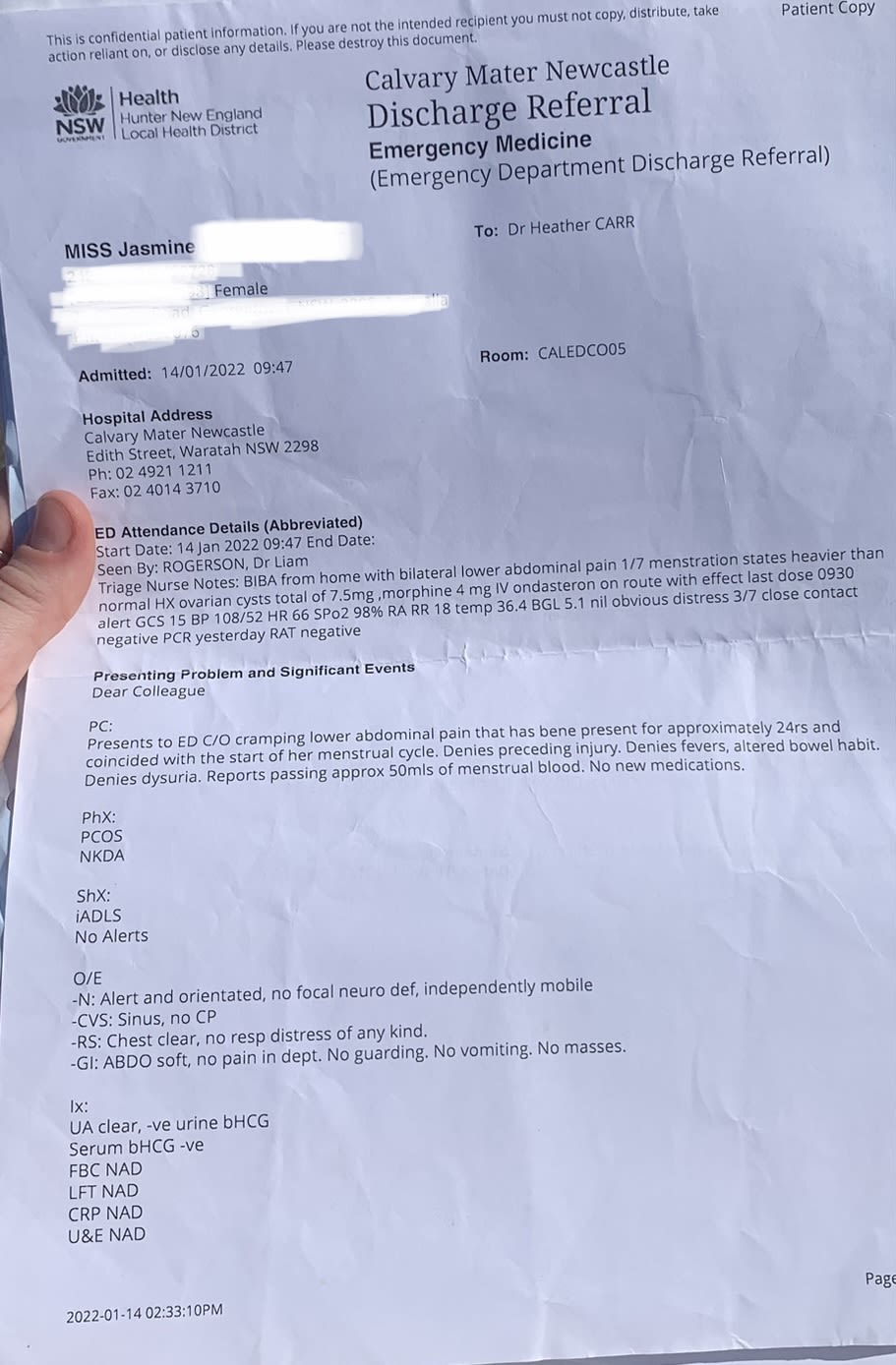

Jasmine

In 2021, after five hours of “laying on the floor in the shower, naked,” and falling unconscious, Jasmine had an ambulance called for the first time.

Giving her morphine, the paramedics asked if she’d felt that pain before.

Jasmine replied, “yeah, all the time.”

Emergency department workers repeatedly told Jasmine to “take a Panadol” and go home. At emergency departments in Australia in 2021-2022, around seven in 10 women presenting with endometriosis-related issues didn't get admitted.

Jasmine saw “probably 10 different” doctors every year since she was 15. They told her to to “learn to manage [her] pain better;” it was “normal”. Some studies have found period pain comparable to a heart attack.

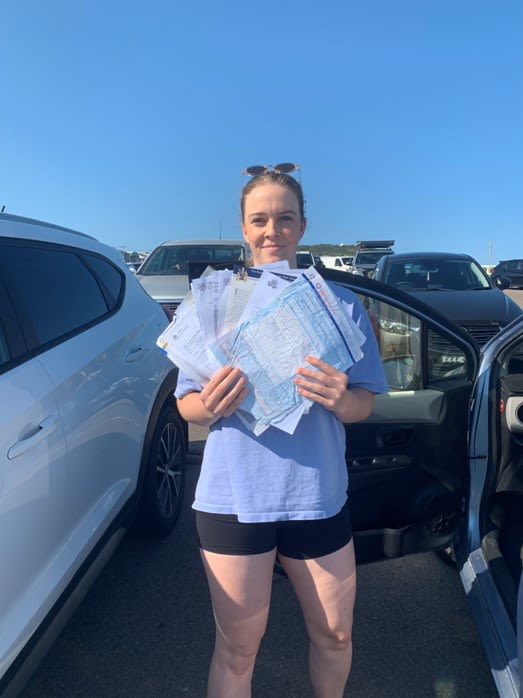

Jasmine's collection of referrals, discharge papers and information from her years of searching for answers. (Supplied: Erin Symes)

Jasmine's collection of referrals, discharge papers and information from her years of searching for answers. (Supplied: Erin Symes)

Jasmine's portable TENS machine to reduce cramping pain. (Supplied: Erin Symes)

Jasmine's portable TENS machine to reduce cramping pain. (Supplied: Erin Symes)

“I did very much feel like it was my fault. I went ‘OK, I'm obviously very bad at managing this. I'm very bad at being a woman’,” - Jasmine.

In 2023, after seven years, a GP finally referred Jasmine to a gynaecologist for the first time. Hearing Jasmine’s symptoms, they booked surgery immediately.

Coming-to after surgery, Jasmine immediately said “please tell me you found it”.

The doctor replied “Yeah. It was a lot worse than we thought”.

She questioned whether years of dismissal caused her to “downplay” her pain. Could she have been more assertive, to be taken more seriously?

Though Jasmine thought she knew what to expect, her surgery still felt “violating”.

“Afterwards you see all the cuts, the wounds everywhere and there's just so much blood.

“It's just so crazy to feel I didn't have any control over that,” she said.

When Jasmine’s surgeon couldn’t completely remove a lesion on her ovary, they impressed its serious implications for her fertility.

“It was all about my right ovary,” Jasmine said.

“What about the fact it was all over my bowels and was here and there?” Children weren’t even something Jasmine was considering yet.

"I just want to manage my pain.

It's about myself, my body,

not my future potential baby...

“Can't we think about me, right now?”

There were 40,500 endometriosis-related hospitalisations in 2021-2022.

Jasmine was terrified of surgery because she’d been so led to believe she didn’t have it. She was actually going to cancel her surgery until her partner of six years said “you have come so far and pushed so hard and fought so hard with so many doctors. Don't give up at the very end.”

“I was led to believe that my pain was dramatic or that I was being silly or that I couldn't cope with it” she said

This reflects a current six-and-a-half-year average delay for women with endometriosis to be diagnosed

For private surgery, Jasmine paid $5000 out of pocket and can now function during her period, with pain relief.

But now Jasmine must manage the disease for the rest of her life. Even going through menopause or a hysterectomy may not bring relief, since endometriosis feeds off oestrogen.

She doesn’t know what’s next.

“I've fought for so long and now it’s kind of the end. It's like, ‘yeah, I've got my diagnosis,’ but now what?” Jasmine said,

"I'm just terrified of it coming back."

"At the end of the day, it’s a disease that doesn’t have a cure and we have to live with it."

- Callie

Taken at the first family meal Kristi could get out of bed for, post-hysterectomy. (Supplied: Kristi Dynes Jørgensen.)

Taken at the first family meal Kristi could get out of bed for, post-hysterectomy. (Supplied: Kristi Dynes Jørgensen.)

In the hospital, post-surgery. (Supplied: Kristi Dynes Jørgensen)

In the hospital, post-surgery. (Supplied: Kristi Dynes Jørgensen)

Kristi

In 2019, Kristi was diagnosed at 36 years old, having symptoms like “troubles with conceiving, pain, lethargy beyond anything I had experienced, bloating, impact to sex life, [and] impact to my step-kids and our relationship.”

She’s now two years post-hysterectomy, which, though “life-changing” for her quality of life, meant “giving up on having kids” and “making the choice to make the best of what I do have”.

Bree

For at least two days a month, Bree would “struggle to get up off the bathroom floor”, with vomiting and stomach problems. In 2019, surgery to remove endometriosis “strangling” her uterus revealed a rare bacterium from a previous surgery. Treatment with seven antibiotics made her miscarry a pregnancy she didn’t know she had. The 27-year-old currently has two kids, both conceived after laparoscopy.

Bree “hopefully” had her last surgery in September this year, with a “full hysterectomy, uterus, cervix, tubes and some more excision” costing $3000 after private health insurance.

Cooper

In 2020, after 10 years in the public system only to receive ablation rather than excision surgery, “making it worse”, Cooper moved private. Despite family history, doctors refused surgery until she “had two emergency appearances within three months for excruciating pain”. Instead, they told her she was “just making things up” through “hysteria” and “depression”. Eventually, a laparoscopy with a general surgeon and a bariatric surgeon found endometriosis on her liver and lungs.

She said public gynaecologists “refused to do anything more than a yearly ultrasound”, which is considered an unreliable tool endometriosis diagnosis. Taking Zoladex treatment was effective but side effects like joint pain, weight gain, no sex drive, lethargy, and physical weakness badly affected her mental health.

Kate

Kate had “unbearable” cramping from age 15. Doctors told her “it’s just your period, everyone has to deal with it”.

Despite finding a 3.5 centimetre cyst on her left ovary, doctors refused to operate until it reached 5 centimetres. In surgery, one and a half years later, surgeons described her lower abdomen as looking “like an endometriosis bomb had gone off”. Since then, Kate has endured six surgeries, “nerve blocking treatments, three-month contraceptive injections, GnRH analogue treatment, a plethora of hormone treatments” and a few miscarriages, which badly impacted her mental and physical health.

Sometimes, Kate prefers to withhold her diagnosis, as “it doesn’t look great for productivity” in a workplace. “I’ve also pushed through severe pain to get to work, for fear of losing my job,” she said.

1 in 6 people with endometriosis have lost their jobs and 1 in 3 people say they’ve been passed over for promotion, due to their endometriosis

"Women make up half of society, and endometriosis is so debilitating.

If men were going through this...

they wouldn't be going through this."

- Jasmine

Dr Gracia Chong (Supplied: Hunter Gynaecology)

Dr Gracia Chong (Supplied: Hunter Gynaecology)

Dr Chong from Hunter Gynaecology agrees that an individual and structural "lack of awareness" is the biggest barrier for women to get an endometriosis diagnosis.

She says it's a "cultural expectation" that women must struggle with their periods, which leads to many women suffering with pain and endometriosis symptoms in silence.

In Dr Chong's opinion, awareness and empowerment is the best treatment for endometriosis, for women to "feel in control through knowledge" and increase diagnosis rates. This includes seeing doctors with empathy and understanding, and finding support groups such as the government's 'EndoZone'. These "fantastic" resources allow women with endometriosis symptoms to be united through "shared experiences", since endometriosis "is a chronic disease... you can't take a tablet and fix it."

"I have definitely felt very dismissed by nine out of 10 doctors that I've met."

- Jasmine

Steph

Steph got her first period at her 12th birthday sleepover party. It was “immediately horrendous”.

Despite her begging, Steph’s mother “refused” to let her take the pill to relieve symptoms, citing “the only reason [Steph] would need that, was if [she] was a ‘slut’ [sic]”.

From the age of 16, Steph was “in an abusive relationship for 10 years”. Her now ex-boyfriend controlled her money and either refused to pay for her GP visits or accompanied her, “to tell the doctor how dramatic [she] was”.

“My ex believed I was making up my pain to avoid sexual activity with him, and would force himself on me.

“My mental health plummeted,” she said.

Steph “pursued a diagnosis more aggressively” after her relationship ended, still encountering dismissive gynaecologists and doctors.

Supplied: Steph

Supplied: Steph

Steph with her mobility aid. (Supplied: surviving.endometriosis on Instagram)

Steph with her mobility aid. (Supplied: surviving.endometriosis on Instagram)

"We talk about how brave Bindi Irwin is, but we don’t talk about how she literally flew to the US for her surgery

because endo care in Australia is so far behind the rest of the world.

"Why don’t we start focusing on the every day people who have lost everything?

"It’s unlikely her experience with endo is anywhere close to mine. She can afford care. I can’t. She doesn’t have the huge emotional weight of 'can I eat this week?' hanging over her. She’s unlikely to be cancelling her specialist and psychologist appointments because she doesn’t have the funds. She has the choice to choose the best surgeons and pay whatever they ask." - Steph

A $15,000 surgery, 17 years after her first symptoms, diagnosed Steph with “severe endometriosis and possible adenomyosis” and deep infiltrative endometriosis lesions.

“My ovaries were twisted by 180 degrees, my uterus was adhered and rotated by 30 degrees”, Steph said.

Her surgeon suspected Steph’s daily pain to be an average person’s eight out of ten. Steph isn’t expected to ever experience below a ‘four’.

Steph developed “fairly severe hospital PTSD” from having an “anaphylactic reaction” to anaesthesia and being “badly mistreated” by a nurse after her suicide attempt. A hospital mistake also means Steph’s IVF journey is halted until she can afford another laparoscopy.

Seventy percent of people with endometriosis must take unpaid time off work to manage their symptoms and Steph sometimes wouldn’t eat for three days straight to “prioritise paying [her] rent and buying cat food”.

Steph lost her $70,000 per year job and lives on a $30,000 disability pension with rent assistance and no superannuation. She has “significant medical debt”, including from over $50,000 in medical procedures alone.

"It's a huge mental health drain not being able to get up and do stuff," Steph says, including leave the house or engage in her old hobbies. She waits for her next surgery and tries to manage her pain by drawing “little uterus monsters”, wondering how she can live the rest of her life like that.

Supplied: surviving.endometriosis on Instagram

Supplied: surviving.endometriosis on Instagram

Supplied: surviving.endometriosis on Instagram

Supplied: surviving.endometriosis on Instagram

Supplied: surviving.endometriosis on Instagram

Supplied: surviving.endometriosis on Instagram

“I would love some more women’s voices to be heard because when I was diagnosed with stage 4 endometriosis, the beginning of this year, I was very uneducated. I felt scared and alone."

- Callie

Once my own 'little monsters', now I wish my surgical scars wouldn’t fade so quickly.

They remind me how brave I was.

Slowing coming-to in the surgery recovery room was the most vulnerable I’ve ever felt, but like Jasmine, all I wanted to know was if they had found endometriosis and justified everything I was going through.

Like so many women, I’m now playing the waiting game.

What will reach us first?

Better research, funding, and awareness?

Or the reoccurring endometriosis?